The health inequality crisis unfolding in Egypt mirrors global trends: the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines is marred by division, inequality, and national and regional self-interest.

As Egypt receives millions of doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, official Egyptian statements could give the impression that the roll-out is going according to plan. However, millions of Egyptians will remain without access to the vaccine for a long time due to governmental disorganisation, nepotism and lack of awareness.

According to the Egyptian Ministry of Health, on 9 May, around 1,300,000 individuals had taken the vaccine out of a population of 100 million (a little less than 2 million according to the World Health Organisation at the time of writing). The slow progress shows a lack of public awareness and trust as health officials announced that even doctors were hesitant to take the vaccine. Despite the government’s control and increasing influence over the media, almost no campaigns have reached out to the population to encourage them to enroll. This leaves an enormous number of people, including the 32% living below the poverty line, unable to register online and receive messages on their mobile phones, unaware of its availability.

“COVID-19 is rampant in Egypt, but it is hard to know exactly how bad the situation is due to underreporting and little official transparency.”

The government’s lack of prioritisation of vaccine distribution exposes Egypt’s inequality, with some people in their 20s able to get their shots while doctors and the elderly are still waiting. This marks a crisis, as around 520 doctors have passed away after contracting the virus. On several occasions, doctors have protested the lack of personal protection equipment and proper treatment if infected. These protest were met with security crackdowns.

Furthermore, in several cases, the government organised the vaccination of students and staff at upper-class universities alongside members of elite social clubs. Members of the government, the House of Representatives, as well as their families, were similarly granted access to the vaccine immediately.

COVID-19 is rampant in Egypt, but it is hard to know exactly how bad the situation is due to underreporting and little official transparency: in summer 2020, even the government admitted that infection rates might be ten times higher than official figures. The slow rate of vaccinations will protract the exposure to new surges of infections in a country with poor health infrastructure: while the 2014 Constitution requires the government to allocate at least 3% of GDP to health, this number barely reached 1.19% in 2019-2020 with a boost to 1.37% at the onset of the pandemic.

Rampant global inequality

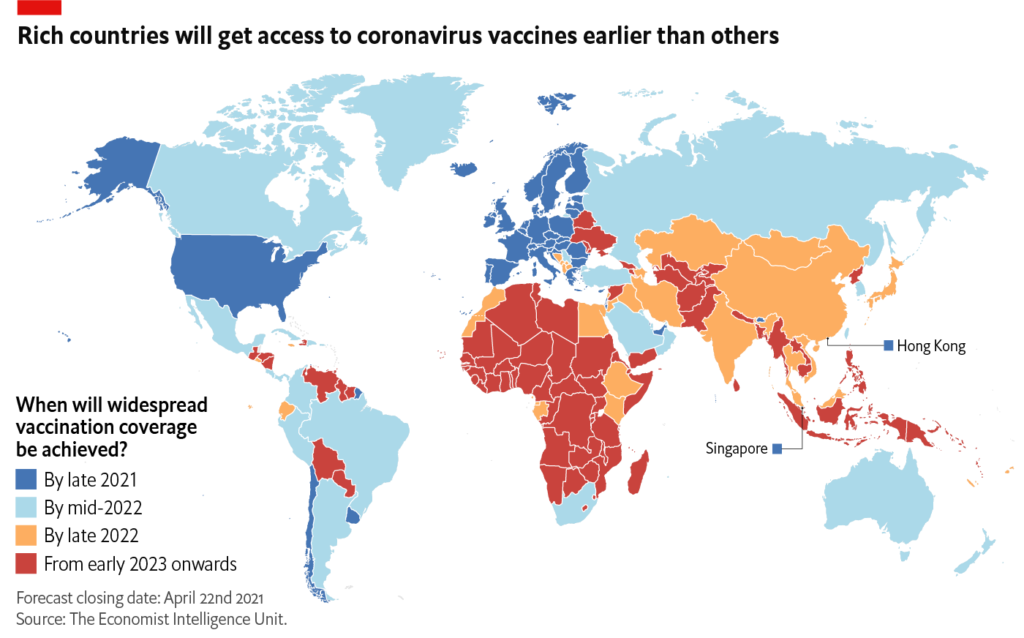

The health inequality crisis unfolding in Egypt mirrors global trends: the roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines is marred by division, inequality, and national and regional self-interest. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), almost 95% of vaccines produced thus far have gone to ten of the wealthiest countries. And while some countries are en route to reopening their societies, the pandemic is on the rise in others, like India.

Affordable, non-discriminatory access to the vaccine is a human right and the international community has, until now, failed in its duty to cooperate to secure that right. Civil society has championed the waiving of intellectual property rights on vaccines to ramp up production and ensure the fastest global roll-out. The WHO has stated, against the claims of pharmaceutical companies, that waiving intellectual property rights and the transfer of technology is crucial.

This proposal has been on the World Trade Organisation’s table since October 2020. The EU only moved following U.S. President Joe Biden’s openness to negotiations on a patent waiver, with the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen declaring she stood ready to “discuss any proposals that address the crisis in an effective and pragmatic manner”. The EU statement marks a positive step for a Union that has historically done everything in its power to strengthen patent rules and secure the interests of the pharmaceutical industry.

But skepticism is warranted. So far, nothing in the way that the European Commission has addressed intellectual property rights during the pandemic indicates a real change of heart. On the contrary, a recent investigation shows that EU Commissioners meet almost exclusively with lobbyists representing the pharmaceutical industry’s interests to the exclusion of critical voices from civil society.

Health is a human right and COVID-19 vaccines should be treated as global public goods. The EU should assume its full responsibility in facilitating global cooperation towards the fastest possible end to the pandemic.

Frederik Johannisson, Economic and Social Rights Programme Officer at EuroMed Rights, with Social Justice Platform, a member of EuroMed Rights’ working group on economic and social rights. Article illustration: The Economist.