Under the pretext of regulating social media networks, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) has submitted on 23 July 2020 a new nine-article legislation proposal to the Parliament Justice Commission. This includes a set of restrictive measures such as the obligation of each social network to have a representative present in Turkey responsible for the removal of illegal content and delivery of user information when requested, the obligation to store Turkey users’ information in Turkey, in addition to a number of other measures aiming to restrain social media usage.

Government officials are claiming that these amendments will ensure that crimes committed on social media platforms will not go unpunished.

However, the legal regulations in Turkey (primarily the Turkish Penal Code, the Anti-Terror Law, and the existing special laws) are currently sufficient for conducting judicial proceedings against alleged crimes committed on the internet. Most often, these laws are already implemented solely for the purpose of censorship. The existing legislative regulations are also used in order to limit freedom of expression and not only to punish perpetrators of hate speech and defamation.

To a very large extent, traditional media remain in the grip of the government, which aims to silence free and independent reporting, citizen journalism and other expressions of social demands. The government leaves no room for divergent discourses.

Online barricades

What lies at the roots of these amendments is the idea of subjecting citizens to stricter surveillance and control. The imposition of such restrictions on multi-user social media platforms introduces the risk of restraint online, including for the personal posts of citizens. Such regulation will not only result in censoring popular social media platforms but also the applications and platforms that users might choose to sign up for in the future.

Among the proposed changes, foreign social media companies with high user traffic face a primary obligation to open a representative office in Turkey and address complaints from authorities within 48 hours. Any non-compliance on the companies’ part could mean measures such as reduction of their bandwidth by up to 90 per cent as well as fines of up to 5 million Turkish Liras (EUR 607,773) as suggested in a circulating copy of the draft law .

As stated by Yaman Akdeniz, cyber rights expert and professor of law at Istanbul Bilgi University, there is already a vastly comprehensive mechanism of censorship and regulations in place. This mechanism already has the authority to block websites such as the National Lottery Administration, Religious Affairs Directorate, The Health ministry, Turkey’s Jockey Club and the Capital Markets Board among others.

Many have compared Turkey’s law with a similar law implemented in Germany, the Network Enforcement Act. However, when comparing Turkey’s social media bill to Germany’s (also known as the NetzDG law with effect from 1 January 2018 to fight against online hatred and extremism) there are a few key differences between the two. Germany’s law doesn’t target news websites while the current provisions of Turkey’s could end up blocking access to Twitter, YouTube and Wikipedia platforms. Blocking requests to specific websites are often politically motivated. According to the data assessed by the NGO Freedom of Expression Association (IFÖD), 6,200 blocking decisions have been issued in 2019 and only 69 were referred to the Constitutional Court.

Another aspect to be considered is that the only legal option to overturn a rejected appeal is to apply at the Constitutional Court. In the case of the blocking of Wikipedia (from 29 April 2017 until 15 January 2020) it took 2 and a half years to the Constitutional Court to decide, on 26 December 2019, to lift the blocking for “violation of basic human rights”. In cases related to online media outlets, the average time to receive a decision from the Court is around 5 years.

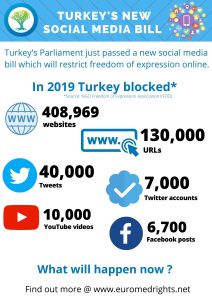

According to the latest IFÖD report , by the end of 2019 a total of 408.494 websites were blocked in the country. Moreover, access was blocked to 130,000 URLs, 7,000 Twitter accounts, 40,000 tweets, 10,000 YouTube videos and 6,200 Facebook content by the end of the year.

Turkey frequently tops Twitter’s list of countries that submit the largest number of requests to remove content or shut down user accounts. The new social media bill might ensure Turkey’s place at the top of this ranking.