In recent weeks, the world battled not one, but two pandemics. Around the world people gasped in horror as George Floyd pleaded for his breath. His passing breathed new life into the fight against racism and thousands around the world took to the streets to denounce systemic racism, discrimination and police brutality.

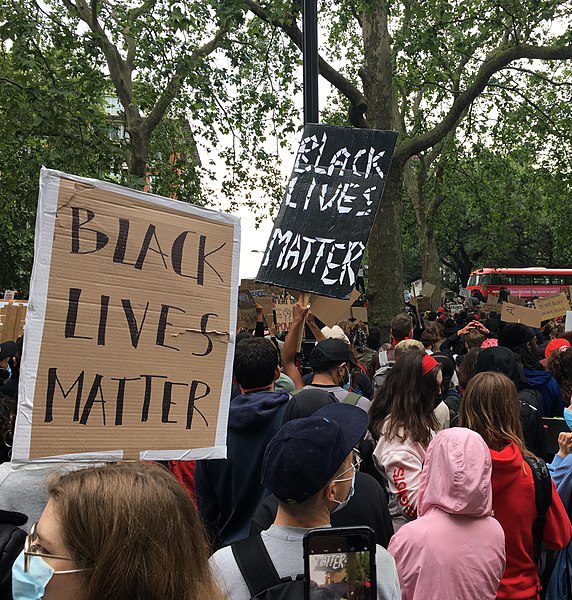

In the United States but also in France, Spain, Italy, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Denmark, Israel, Tunisia and Turkey, tens of thousands of citizens shouted out their demand to fight against police violence, institutionalised racism and racial discrimination. Citizens showed solidarity with the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement. But their requests went beyond a simple show of solidarity. They also refuse to see decision-makers in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East turn away from their countries’ own histories and realities of racism.

A long overdue debate in the region

The Mediterranean has always been a place where different cultures met and blended. However, such wealth of diversity has not prevented racist behaviours. Systemic racism exists in the EuroMed region and unfolds in different ways. It is most evidently seen when discrimination is enshrined and/or facilitated by legislative frameworks. In Lebanon for instance, the kafala system that governs entry, residence and work for migrant domestic workers, results in severe violations of human rights. Under this system, which disproportionately impacts migrant women, domestic workers are tied to their employers and excluded from the Lebanese Labour Law. This leads to various and systematic economic, social, and sexual abuses.

“51.1% of sub-Saharan migrants were victims

of hate and racist acts in 2019 in Tunisia”

In Tunisia, racist attacks, prejudices and insults against the black community and settled migrant populations from sub-Saharan Africa or elsewhere are commonplace, while reports to the police are regularly ignored. The law on elimination of all forms of racial discrimination was only promulgated on 9 October 2018 following years of advocacy from civil society organisations. This was the first time a country from the MENA region adopted such a law.

But racial violence continues to increase. In 2019 in Tunisia, 51.1% of sub-Saharan migrants were victims of hate and racist acts. These acts consist mainly of insults (89.60%), physical violence (33.90%), scams (29.60%), violations (22.90%), blackmail (7.80%) and lack of respect (4%). This alarming situation underlines a lack of political will to implement the mechanisms created to enforce the law, such as the National Commission for the Fight against Racial Discrimination.

In Israel/Palestine, the situation is marked by the decades of dispossession, occupation and discrimination Palestinians have been subjected to by Israeli policies. The disproportionate and systematic violence used by Israeli forces against the Palestinian population is routine. This is evidenced most recently by the security forces’ killing of Iyad Halak, an unarmed, autistic man. According to the human rights group BT’selem, investigations into the killings of more than 200 Palestinians by the army during the past nine years have resulted in only three soldiers being convicted.

At the same time, Black Palestinians and Black Israelis continue to face racial discrimination in various daily situations. The 53-year-old military occupation and the gradual enshrinement of Jewish supremacy in Israeli law are further examples of how groups and peoples can be subjugated in the Israeli/Palestinian mosaic.

Europe: the elephant in the room

European countries are certainly not to be outdone. According to a 2019 report by the EU’s Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), in the five years before the survey nearly one in three Black people experienced racist harassment, one in four felt racially discriminated against when looking for work and one in five were subject to discrimination when looking for housing in the EU.

Even when a policy or a law supposedly does not discriminate and applies to everyone equally, it may still impact on certain groups more than on others. In Spain, migrants have been excluded for years from many healthcare services. 28% of migrant women hold a university degree, compared to 28.3% of Spanish women. Yet, they are still over-represented in low-skilled jobs. The same situation applies in Denmark where, despite high rates of overqualification among immigrants and ethnic minorities, they remain under-represented in management positions.

Racist behaviours also fuel violence. In France, the Defender of Rights (“Défenseur des Droits” [Editor’s Note: akin to a Rights Ombudsman]) reports that young men perceived to be of Black or North African descent are twenty times more likely to be controlled and questioned by the police. The number of arbitrary detentions and the level of police brutality enacted against young men of Black and North African descent in the country has been denounced by international institutions and civil society for years. This is unfortunately not a French-specific issue. Most recently, in Belgium, a Black member of the European Parliament was humiliated by the police.

Racialised policing, as well as the (often) excessive use of police force which accompanies it, is experienced systematically on both shores of the Mediterranean. It is a gendered and racialised phenomenon, operated by a male-dominated profession, disproportionately impacting young racialised men. Profiling strategies, statistics on arrests along racial or ethnic lines, and the higher proportion of racialised lives which are ended by police actions demonstrate the racism inherent to national systems.

The EU border, a textbook case for institutionalised racism

Migrants and refugees are a case in point. Institutional racism best manifests itself in EU border management and specific migration policies implemented by Member States. These are based on the racist assumptions that migrants’ lives, especially when they are not White, are not worth saving. Migrants are left to drown at sea, violently pushed back at land borders or left to die in Libya’s detention centres. For example, as of 30 April 2020, a total of 3,078 migrants were intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard off the Libyan coast and brought back to Libya.

Brutal police violence is also used at the borders as a form of punishment, degrading treatment and deterrent. Numerous reports, evidence and testimonies document the level of abuse, torture and routine violent pushbacks that remain unpunished, for example in Croatia, Calais and Ventimiglia, to name but a few.

“Brutal police violence is used at the borders as a form of

punishment, degrading treatment and deterrent”

However, the absence of physical violence at a country’s border does not entail an absence of racism. Denmark, for instance, is exploring possibilities to reach an agreement with Serbia or other third countries on establishing a deportation centre for rejected asylum seekers. In Morocco, refugees and migrants in transit from Sub-Saharan Africa face racism in all areas of life, be it housing, education or employment. In France, the children of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa are impacted twice as much by unemployment and earn on average 15% less.

Which way forward now?

The current anti-racism movement reminds us that our societies have not (sufficiently) confronted and processed histories and realities of systemic racism. These movements also bring to the fore a denial or lack of political will to address it.

But these are conversations we need to have, at all levels, if we are to improve the lives of racialised people who are entitled to equality and freedom from discrimination, two fundamental human rights principles. This needs to start by challenging national narratives; updating school curricula and teaching methods; gathering race/ethnicity-disaggregated data; tackling spatial segregation, police violence and racism within state institutions; guaranteeing the rights of migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees; introducing and fully implementing non-discrimination laws, including combatting impunity for racist harassment and crimes; and finally ensuring representation at all levels of decision-making.

As a Euro-Mediterranean human rights network, we are committed to increase our efforts and work closely with our members across the region calling for an end to systemic racism and police violence.

We, as civil society organisations, have a responsibility to remind decision-makers of their duties to work towards an equal and just society.

It starts now.

Wadih Al-Asmar

President of EuroMed Rights